For most British football fans looking back at the 90s, years that end in odd numbers usually represent summers without international tournament football that would otherwise bridge the gap between League campaigns.

The summer of 1995 is remembered rather more fondly in the town of Blackburn, as their football club had just completed its most memorable season to date. As the team travelled through the streets in an open top bus, they held aloft the Premier League trophy with fans gazing on in elation and wonderment, pinching themselves to make sure this was indeed actually happening. They had grown to love this side, who had been hastily assembled yet managed to demonstrate the blue collar work ethic associated with the Lancashire industrial town, as well as challenge England’s more established football clubs with a confident assurance.

While football fans can be forgiven for being caught up in the moment and letting the occasion soak in, those in charge of the direction of a football club have an altogether different duty. Becoming Champions of any sport requires a recalibration of expectations, as going from the hunter to the hunted brings about a different set of challenges entirely. Unfortunately for Blackburn what should have been a time for future planning turned into an over-reliance on the past, and the story of season 95/96 is a cautionary tale for any football club coming to grips with accelerated success.

To help us understand Blackburn Rovers rise to the top of the English game we should begin with the owner’s origin story. Lancashire businessman, and lifelong Blackburn Rovers supporter, Jack Walker was reported to have donated materials to assist with the reconstruction of Ewood Park in the late 80s, at which point discussions began about a potential purchase of the club. Having decided to sell his Steel business in early 1990, Walker would use the proceeds to take over the ownership of Blackburn Rovers in January of 1991.

The Take Over

At this time Blackburn found themselves in 18th position of the old English Division 2, averaging crowds of around 8,000 per week. They hadn’t tasted top division football since 1966 and throughout the 70s Rovers would spend a few years in Division 3, so for Blackburn’s newly found wealth to translate into better results on the field Walker had to assemble a back-room team capable of bringing legitimacy to the club.

Blackburn’s manager at the time was Don Mackay, a Scottish coach who had been at the club for three seasons after having served his apprenticeship under Graeme Souness and Walter Smith as 1st team coach at Rangers in the mid-80s. He would guide Blackburn to safety after a poor start to the 90/91 season, but in October of the following season he would be replaced by one of English footballs leading managers.

It seems almost other worldly that a figure such as Kenny Dalglish would drop down a division to take over at Blackburn Rovers, but this was a move that would pay immediate dividends as he gained promotion at the first time of asking.

His first signing saw the return of Colin Hendry from Man City, who was later joined by Gordon Cowans from Aston Villa and Mike Newell from Everton. A 6th place finish at the end of season 91/92 would see Blackburn qualify for the playoffs, where they would progress past Derby County by an aggregate score of 5-4 before meeting Leicester in the playoff final at Wembley Stadium.

A Mike Newell penalty on the stroke of half time was enough to give Blackburn a 1-0 victory, which ensured promotion into the inaugural FA Premier League season of 92/93.

During the next 18 months Dalglish put in place the building blocks of a side that would become synonymous with the club’s success throughout this era. His recruitment focused on some of England’s most promising youngsters, the most notable of which was the capture of Alan Shearer from Southampton who joined despite the advances of Manchester United. Shearer was joined that summer by Stuart Ripley from Middlesbrough, Graeme Le Saux from Chelsea and Tim Sherwood from Norwich. Dalglish also signed two Scandinavian defenders, Henning Berg from Lillestrom and Patrik Andersson from Malmo. While Berg went on to have an illustrious career in English football, Andersson would need to leave in order to realize his potential, as later moves to FC Bayern and FC Barcelona would prove.

Blackburn finished in 4th place at the end of 92/93, marking their first year back in the topflight with a very respectable finish and narrowly missing out on European football to Norwich by a single point. The following summer Dalglish strengthened his squad once more, spending well over 10M pounds on Tim Flowers from Southampton, David Batty from Leeds United, Paul Warhurst from Sheffield Wednesday, Kevin Gallacher from Coventry City and Ian Pearce from Chelsea.

93/94 was the year that Blackburn fully asserted themselves as a genuine title contender, removing any doubt they were a flash in the pan as they fought valiantly with Manchester United throughout the entirety of the season.

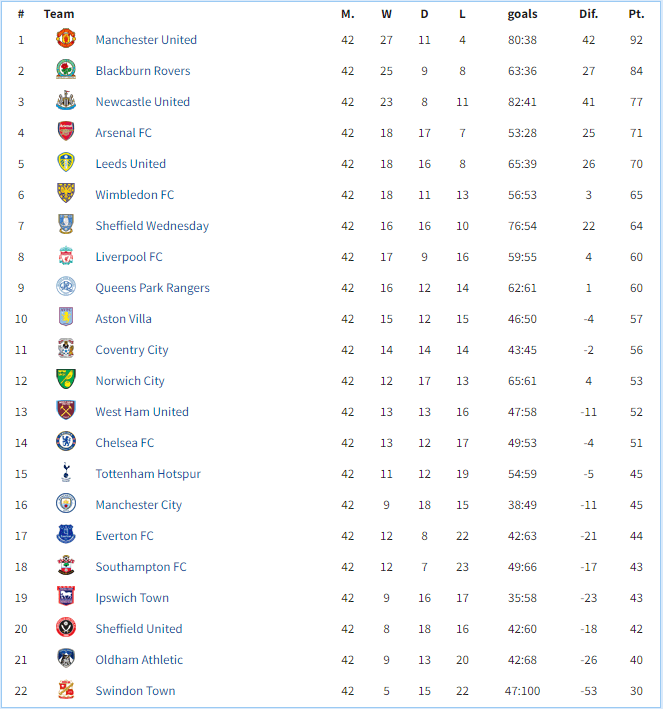

Despite beating Alex Ferguson’s side to go within three points of top spot in April of 1993, United’s experience saw them pull away in the final few weeks of the campaign to win the Premier League title by 8 points.

Dalglish returned for the 94/95 season with a renewed focus on going one step further in the title, which was backed up by Jack Walker in July of 1994 when he sanctioned a move for Chris Sutton from Norwich City for a record British transfer fee of 5M pounds. Dalglish’s starting lineup was now complete, but the cost in which it had been assembled would see the balance tip from hope now into expectation.

After 10 matches Blackburn found themselves in 3rd position behind the newly promoted duo of Frank Clark’s Nottingham Forest and Kevin Keegan’s Newcastle United. Rovers class would soon prevail as they went on a run of 11 wins in 14 matches, losing only to perennial title challengers Manchester United. While Alex Ferguson’s side were still capable of showing up in the big games, their highly inconsistent form throughout much of 94/95 contributed toward Blackburn opening an 8-point lead by mid-April.

In what could be described as a lack of nerve, Blackburn’s form dipped and they closed out April by taking only four points from four matches. United capitalized by going on a winning run of their own, setting up a final day showdown with only two points separating the sides.

Both teams faced an away trip to close out the season, with United headed to Upton Park to take on 13th placed West Ham United and Blackburn travelled to Anfield to face 5th placed Liverpool. Alex Ferguson’s mind games were in full effect in the days running up to the matches, claiming that Liverpool’s allegiances with Dalglish would prove a factor in deciding the result. Yet it was his own sides result that ultimately decided the day’s events, as United could only muster a 1-1 draw with West Ham rendering the result at Anfield redundant. Naturally, during the course of the game emotions ran high as Blackburn fans looked on anxiously as Liverpool’s John Barnes cancelled out Alan Shearer’s opener, while news filtered through of a Brian McClair equalizer at Upton Park to bring United back level.

In the closing moments of the match Jamie Redknapp would score from a wonderfully struck free kick to give Liverpool a 2-1 victory, yet moments after the goal Blackburn supporters simultaneously celebrated as they found out Manchester United had failed to beat West Ham. In what will be remembered as one of the Premier League’s most memorable closing days, Blackburn Rovers were crowned Champions of England for the first time since 1914.

After the match a clearly emotional Kenny Dalglish spoke with Sky Sports of his joy at completing the task that he and Jack Walker had set out to do in 1991. Not only had he skillfully assembled a group of players that complemented each other’s talents, he had also managed to foster a belief within a provincial club that had saw overcome the elite and achieve English footballs’ top prize.

Join us next time as we delve deeper into what began as a summer of delight, but ended in despair.